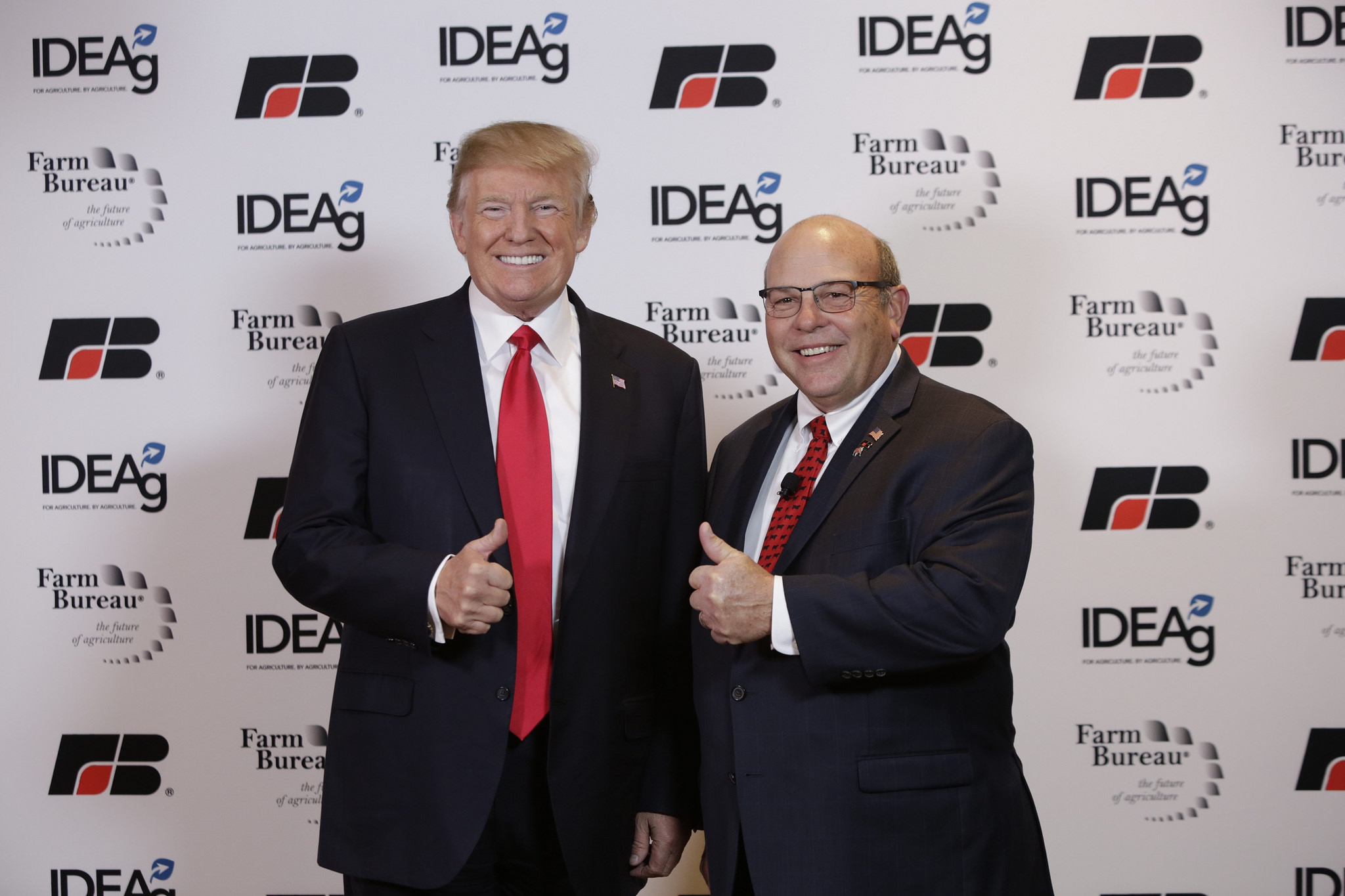

The USMCA trade agreement officially went into effect this week. You’d be forgiven for missing the news.

On July 1, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, took effect, bookmarking one of President Trump’s signature campaign promises: a replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The USMCA, the mammoth deal governing virtually all trade between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, has been in the works since the early days of Trump’s presidency, and it’s won broad support from food and agriculture groups. Trump called NAFTA “perhaps the worst trade deal ever made,” vowing to renegotiate the deal with more favorable terms for U.S. companies. As the New York Times reported on Wednesday, there’s still a lot to iron out—key provisions, like stronger labor protections for Mexican workers, have yet to come to fruition.

The agreement addresses some long-term sore spots for U.S. farmers, opening up new avenues for dairy exports to Canada and attempting to force Mexico to allow imports of genetically modified crops. Other food-related provisions are relatively minor, the products of “side letters,” which are basically bonus agreements between two countries that clarify issues like whiskey sales and cheese names.

Here are some of the changes, major and minor, for U.S. producers and consumers:

1. A California wine aisle in British Columbia

A side letter between U.S. and Canadian trade officials mandates that the 29 grocery stores in British Columbia which only sell locally sourced wine must begin stocking wine made in the U.S. As the Vancouver Sun reports, there are 1,100 other wine and liquor stores in the area that sell alcohol from around the world, so the addition of another couple dozen won’t substantially change the drinking habits of too many Canadian oenophiles. And as Politico reports, Canadian vineyards are likely not too concerned—a host of other regulations still give domestic wine a home court advantage.

2. GMOs in Mexico

Though it’s technically already legal for genetically modified products to be sold—but not grown—in Mexico, the Mexican government has been slow to approve import permits for things like GM corn. That might change with USMCA: Last month, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said he’d use some language in the agreement to force Mexico to approve these products. The USMCA has also sparked concern among Mexican farmers, environmentalists, and anti-GMO advocates because it may crack open a door for biotechnology companies to patent Mexico’s native corn varieties and eventually challenge a ban on planting genetically modified corn in the country. Here’s an explainer from Food and Power on how that could happen.

3. Parmesan by any other name ….

One of the side letters between the United States and Mexico affirmed a list of cheese names that can be used without restriction in each country, including Gouda, Havarti, Mozzarella, and others. Yet there are a few conspicuous absences: Feta, Parmesan, and Asiago did not make the list. That’s because the European Union has sought to protect those names, insisting that Parmesan can only come from Parma, and Greeks have a lock on proper feta. Mexico will not market U.S. cheese imports labeled with these names, though the U.S. will continue to allow domestic cheesemakers to call their products what they like. Dairy bigwigs, largely pleased with the deal, are still a little cheesed off about the omissions, telling Food Dive that it appeared the EU had “just done a better job of negotiating” with Mexico, and that changing labels on American-made parm would be a “pretty hard hit.” What this means, in practice, is that Kraft can’t sell it’s Parmesan canisters in Mexico without calling them something else, like “Parmesan-inspired” or “Salted Wood Pulp.”

4. More dairy to Canada, but still too much dairy

The U.S. and Canada have fundamentally different approaches to regulating dairy production. In the U.S., farmers produce as much as they can sell, and the government subsidizes the industry regardless of production levels. By contrast, Canada operates under a supply management system, in which the government sets production levels for the nation’s dairy supply. It may sound strange, but it guarantees farmers will have a market for their product and that they can break even when they sell it. (Supply management has actually drawn some interest from American producers in recent years as milk prices have fallen below the cost of production.) Anyway, U.S. producers—and Trump—have long wanted to sell more of their excess U.S. dairy to Canada, and they’ve found a win with USMCA: Canada raised the percentage of dairy it will import from the U.S. as part of the new trade agreement. Counter reporter Sam Bloch penned an explanation on this phenomenon back in 2018, but this takeaway from one Canadian dairy producer kind of says it all: “It’s not going to resolve any of their issues, but they have another dumping ground for their surplus product.”

5. Labeling recognition for American Rye Whiskey, regional mezcals, and “the rum of Mexico”

Another side letter between the U.S. and Mexico agrees to start adding new booze categories to the list of liquors recognized by each country. Already, in the U.S., all bottles labeled “tequila” and “mezcal” must come from Mexico. Similarly, in Mexico, anything you find labeled “bourbon” or “Tennessee whiskey” will have been distilled in the U.S. The side letter specifies that American Rye Whiskey sold in Mexico will come only from the U.S., and the U.S. will recognize Bacanora, Sotol, and Charanda. The first two spirits are regional mezcals, and Charanda is known as “the rum of Mexico” and must be made from sugar cane grown at or above 1,500 meters over sea level. According to The Mazatlan Post, the high elevation and volcanic soil give the sugar cane a distinctive flavor and higher sugar content.